The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (December 10, 1948), which we commemorate today, was a response to the horror and barbarity of war. But that was merely a propitious occasion to finally recognize them universally. They are not the product of political consensus but rather the expression of something prior: human dignity.

Leo XIV affirmed in his apostolic exhortation on love for the poor, Dilexi te, that human dignity admits no postponements or conditions; it must be present, absolute, and non-negotiable.

Human rights do not grant us dignity, but rather protect it; they are its guarantors. Dignity does not depend on laws or organizations. From a Christian perspective, it has a profound foundation: we are made in the image of God, children of the Father, temples of the Holy Spirit, capable of relating to Him, co-creators and transformers of the world.

That is the greatness of being human, and no other power can grant or take it away. It is not lost; it is independent of how we feel, how we act, or how we behave. Even if we misuse our abilities, have diminished abilities, or fail to act in a way that is consistent with that dignity, we do not lose it.

Measuring worth by success or power is contrary to that dignity. Today, it may seem outdated to some, revolutionary to others, to defend the idea that we are made in the image of God. Every person, regardless of their circumstances, carries a light that no shadow can extinguish.

Defending human rights, in this sense, is to safeguard that divine reflection in every face. That is why the Church does not “sign” human rights as if they were concessions: because what is granted one day can also be taken away.

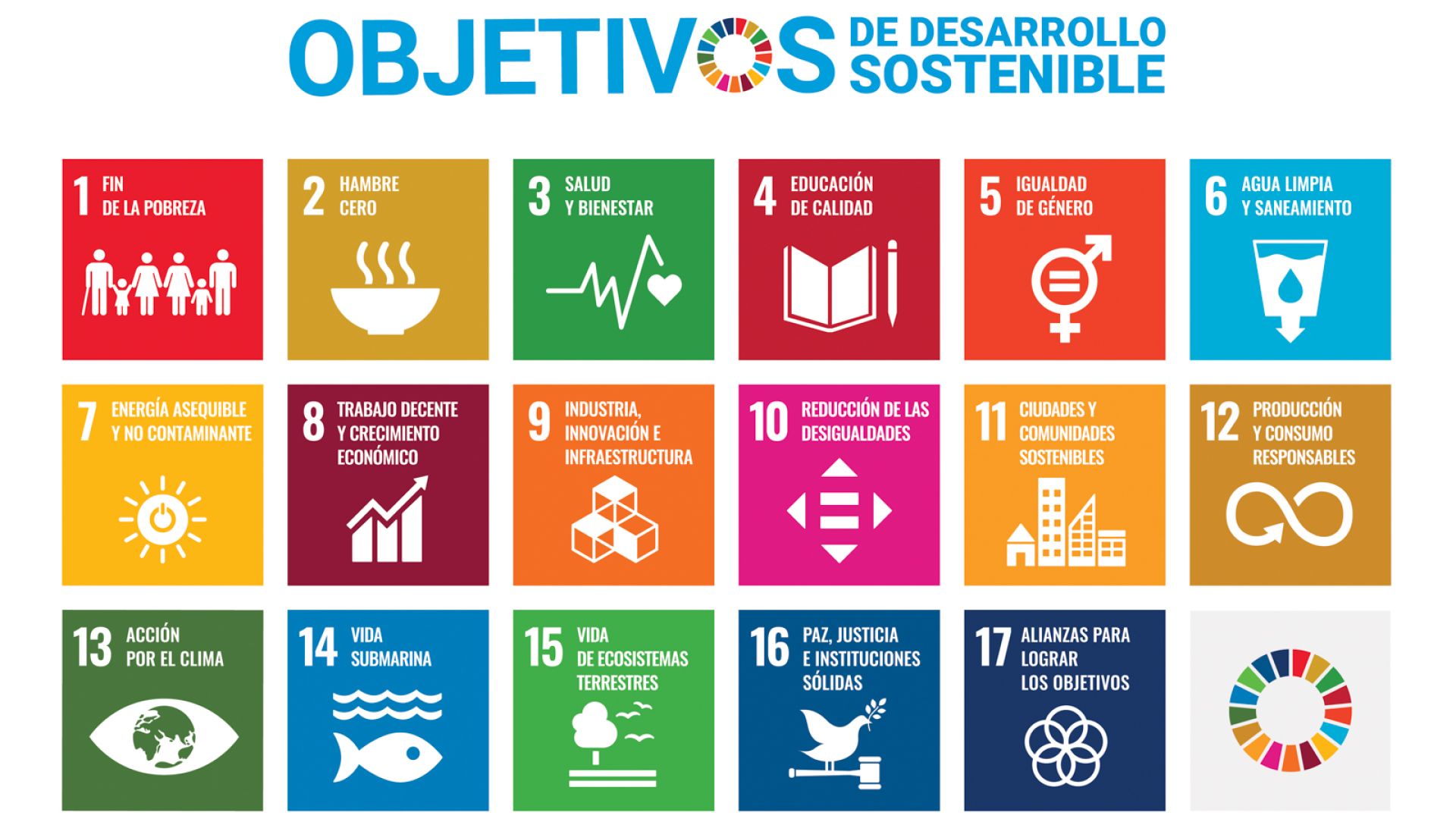

There is a shadow of doubt currently that hangs over the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which originated as a global commitment to eradicate poverty, protect the planet, and ensure peace and prosperity. They are an update of the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights in the form of a concrete action plan.

The SDGs are responses to injustices, but they also reflect the yearning for a full life. The Church and its social and solidarity organizations see the SDGs as a political and social translation of the values of the Kingdom proclaimed by Jesus, which is not an abstract concept, but the concrete promotion of greater justice, fraternity, and ecological sustainability.

When the international community commits to guaranteeing rights such as education, health, equality, and peace, it is working—even if it doesn’t call it that—for what God dreamed for humanity: that no one is excluded, that life is defended, that the earth is cared for.

The core of the SDGs aligns with the Gospel: to dignify human beings and restore harmony with creation. It is not merely a social task, but also a way of collaborating with God’s plan. Defending Human Rights and all their manifestations (Universal Declaration, SDGs) is not simply a social act, but an encounter with God’s plan.

Says Leo XIV in the document already cited: “We are not in the horizon of charity, but of Revelation; contact with those who have no power or greatness is a fundamental way of encountering the Lord of history.”

Society is called to action on this day; and the Church is called to spread the values of the Kingdom. It is a collective and shared commitment. For those of us who believe, this day is an opportunity to defend God’s plan: that every life be dignified, free, and fulfilling.